Click Here to download “Work Fulfillment by Family Structure and Religious Practice”

Work Fulfillment by Family Structure and Religious Practice

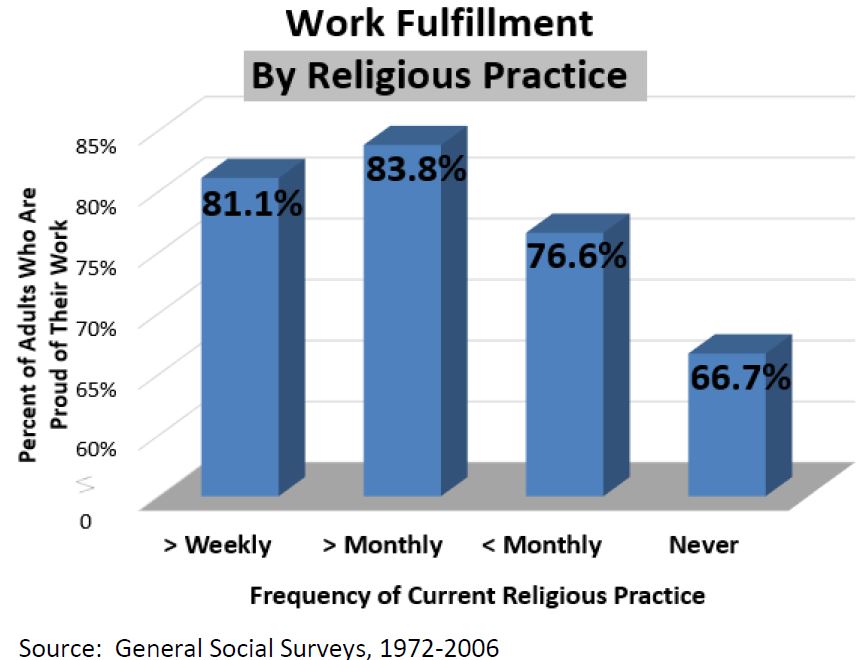

Family Structure: According to the 1972-2006 General Social Surveys, [1] 85.9 percent of married, previously-divorced adults were proud of the type of work they do, followed by 84.4 percent of always-intact married adults; however, the difference is only one and one-half percentage points. There is a significant gap between these two groups and single adults. Of the latter, 74 percent of divorced or separated single adults and 65.8 percent of never-married single adults are proud of the type of work they do. The typical pattern is for those in intact marriages to score highest on outcomes. Here they score second highest, the difference being a statistically non-significant one and one-half percentage points. However, as the evidence indicates, adults who are married (always-intact and remarried) tend to take greater pride than singles in the type of work they do. Religious Practice: The 1972-2006 General Social Surveys shows that 83.8 percent of adults who worshipped between one and three times a month took the greatest pride in the work they do, compared to 81.1 percent of those who worshipped at least weekly, 76.6 percent of those who attended religious services less than once a month, and 66.7 percent of those who never attended religious services.

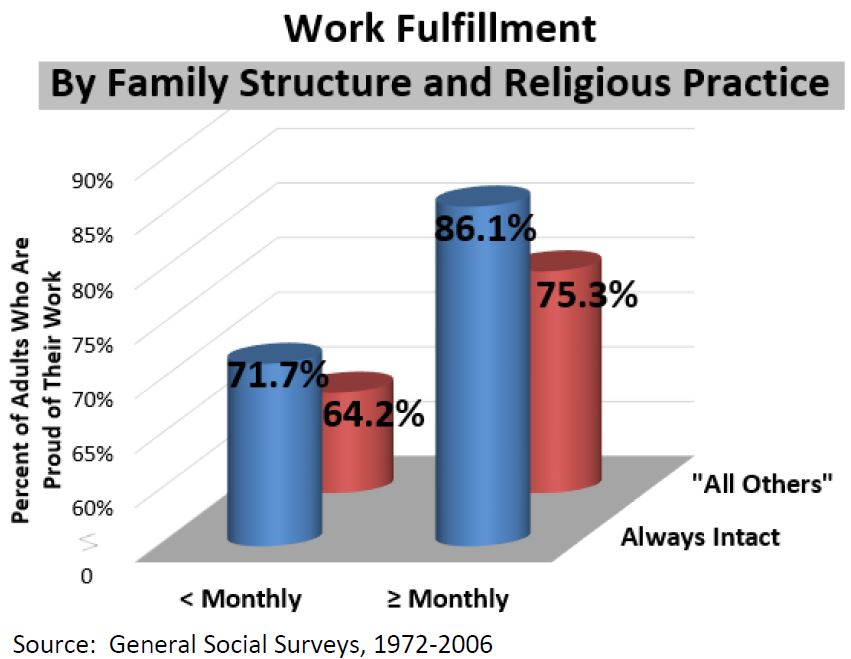

The typical pattern regarding the impact of religious observance on positive outcomes is that those who worship most frequently do best. In this case, those in the second group (one to three times a month) do better, though by only two percentage points, than those who worshipped weekly or more. It is worth looking at the third chart in this series, religious attendance and marriage combined, to note that those in intact families who worshipped weekly took the most pride in their work.

As these data show, adults who worship at least monthly are more likely to be proud of the type of work they do.

Religious Practice: The 1972-2006 General Social Surveys shows that 83.8 percent of adults who worshipped between one and three times a month took the greatest pride in the work they do, compared to 81.1 percent of those who worshipped at least weekly, 76.6 percent of those who attended religious services less than once a month, and 66.7 percent of those who never attended religious services.

The typical pattern regarding the impact of religious observance on positive outcomes is that those who worship most frequently do best. In this case, those in the second group (one to three times a month) do better, though by only two percentage points, than those who worshipped weekly or more. It is worth looking at the third chart in this series, religious attendance and marriage combined, to note that those in intact families who worshipped weekly took the most pride in their work.

As these data show, adults who worship at least monthly are more likely to be proud of the type of work they do.

Family Structure and Religious Practice Combined: The adults who took the greatest pride in the work they do were those in always-intact marriages who also worshipped at least weekly (86.1 percent). The next largest percentage was all other adults who worshipped at least weekly (75.3 percent), followed by adults in always-intact marriages who never attended worship services (71.7 percent) and all other adults who never attended religious services (64.2 percent).

Family Structure and Religious Practice Combined: The adults who took the greatest pride in the work they do were those in always-intact marriages who also worshipped at least weekly (86.1 percent). The next largest percentage was all other adults who worshipped at least weekly (75.3 percent), followed by adults in always-intact marriages who never attended worship services (71.7 percent) and all other adults who never attended religious services (64.2 percent).

Related Insights from Other Studies: Several other studies corroborate the direction of these findings. Louis Levy-Garboua of the University of Paris and Claude Montmarquette of the University of Montreal reported that religion has a positive influence on job satisfaction among Canadian workers.[2]

In a study of nurse administrators, Vickie Lee of Troy State University and Melinda Henderson of Florida State University found that “highly committed respondents reported strong religiosity.”[3]

Stacy Rogers and Dee May of the Pennsylvania State University found “increases in marital satisfaction contributing significantly to increases in job satisfaction over time” and, conversely, “increases in marital discord significantly relating to declines in job satisfaction over time.”[4]

Michael Shields of the University of Liecester and Melanie Ward of the Institute for the Study of Labor also reported that, among English nurses, being married has a positive effect “on overall job satisfaction.”[5]

Several other studies corroborate the direction of these findings. Lilia Meltzer and Loucine Huckabay of the California State University, Long Beach found in a study of critical care nurses that 70 percent of their sample was married and 68.3 percent of their sample “indicated that religion was very important in their lives.” Their results also “suggest that nurses who viewed religion as important in their lives experienced fewer feelings of emotional exhaustion when confronted with ethical dilemmas than did nurses for whom religion was not so important.”[6]

Louis Lévy-Garboua of the University of Paris and Claude Montmarquette of the University of Montreal found that religion has a positive influence on job satisfaction and that marital status also affects job satisfaction among Canadian workers.[7]

[1] These charts draw on data collected by the General Social Surveys, 1972-2006. From 1972 to 1993, the sample size averaged 1,500 each year. No GSS was conducted in 1979, 1981, or 1992. Since 1994, the GSS has been conducted only in even-numbered years and uses two samples per GSS that total approximately 3,000. In 2006, a third sample was added for a total sample size of 4,510.

[2] Louis Levy-Garboua and Claude Montmarquette, “Reported Job Satisfaction: What Does It Mean?” Journal of Socio-Economics 33 (2004): 135-51.

[3] Vickie Lee and Melinda Henderson, “Occupational Stress and Organizational Commitment in Nurse Administrators,” The Journal of Nursing Administration 26 (1996): 21-28.

[4] Stacy J. Rogers and Dee C. May, “Spillover between Marital Quality and Job Satisfaction: Long-Term Patterns and Gender Differences,” Journal of Marriage and Family 65 (2003): 482-95.

[5] Michael A. Shields and Melanie Ward, “Improving Nurse Retention in the National Health Service in England : The Impact of Job Satisfaction on Intentions to Quit,” Journal of Health Economics 20 (2001): 677-701.

[6] Lilia Susana Meltzer and Loucine Missak Huckabay, “Critical Care Nurses’ Perceptions of Futile Care and Its Effects on Burnout,” American Journal of Critical Care 13 (2004): 202-8.

[7] Louis Levy-Garboua and Claude Montmarquette, “Reported Job Satisfaction: What Does It Mean?” Journal of Socio-Economics 33 (2004): 135-51.]]>

Related Insights from Other Studies: Several other studies corroborate the direction of these findings. Louis Levy-Garboua of the University of Paris and Claude Montmarquette of the University of Montreal reported that religion has a positive influence on job satisfaction among Canadian workers.[2]

In a study of nurse administrators, Vickie Lee of Troy State University and Melinda Henderson of Florida State University found that “highly committed respondents reported strong religiosity.”[3]

Stacy Rogers and Dee May of the Pennsylvania State University found “increases in marital satisfaction contributing significantly to increases in job satisfaction over time” and, conversely, “increases in marital discord significantly relating to declines in job satisfaction over time.”[4]

Michael Shields of the University of Liecester and Melanie Ward of the Institute for the Study of Labor also reported that, among English nurses, being married has a positive effect “on overall job satisfaction.”[5]

Several other studies corroborate the direction of these findings. Lilia Meltzer and Loucine Huckabay of the California State University, Long Beach found in a study of critical care nurses that 70 percent of their sample was married and 68.3 percent of their sample “indicated that religion was very important in their lives.” Their results also “suggest that nurses who viewed religion as important in their lives experienced fewer feelings of emotional exhaustion when confronted with ethical dilemmas than did nurses for whom religion was not so important.”[6]

Louis Lévy-Garboua of the University of Paris and Claude Montmarquette of the University of Montreal found that religion has a positive influence on job satisfaction and that marital status also affects job satisfaction among Canadian workers.[7]

[1] These charts draw on data collected by the General Social Surveys, 1972-2006. From 1972 to 1993, the sample size averaged 1,500 each year. No GSS was conducted in 1979, 1981, or 1992. Since 1994, the GSS has been conducted only in even-numbered years and uses two samples per GSS that total approximately 3,000. In 2006, a third sample was added for a total sample size of 4,510.

[2] Louis Levy-Garboua and Claude Montmarquette, “Reported Job Satisfaction: What Does It Mean?” Journal of Socio-Economics 33 (2004): 135-51.

[3] Vickie Lee and Melinda Henderson, “Occupational Stress and Organizational Commitment in Nurse Administrators,” The Journal of Nursing Administration 26 (1996): 21-28.

[4] Stacy J. Rogers and Dee C. May, “Spillover between Marital Quality and Job Satisfaction: Long-Term Patterns and Gender Differences,” Journal of Marriage and Family 65 (2003): 482-95.

[5] Michael A. Shields and Melanie Ward, “Improving Nurse Retention in the National Health Service in England : The Impact of Job Satisfaction on Intentions to Quit,” Journal of Health Economics 20 (2001): 677-701.

[6] Lilia Susana Meltzer and Loucine Missak Huckabay, “Critical Care Nurses’ Perceptions of Futile Care and Its Effects on Burnout,” American Journal of Critical Care 13 (2004): 202-8.

[7] Louis Levy-Garboua and Claude Montmarquette, “Reported Job Satisfaction: What Does It Mean?” Journal of Socio-Economics 33 (2004): 135-51.]]>