Click Here to download “Teen Pregnancy and Family Response by Family Structure and Religious Practice”

Teen Pregnancy and Family Response by Family Structure and Religious Practice

Wave 1 of the National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health (Add Health)

[1] found that adolescents aged 13 to 19 in intact families that worshipped weekly or more were most likely to strongly agree that a pregnancy would embarrass their family.

[2]

Family Structure: Teens in intact married families were most likely to report that getting pregnant (or getting someone pregnant) would embarrass their family (39.4 percent). They were followed by adolescents in cohabiting stepfamilies (32.3 percent), married stepfamilies (31.5 percent), single divorced parent families (28.4 percent), always-single-parent families (24.5 percent), and intact cohabiting families (21.3 percent).

Religious Practice:

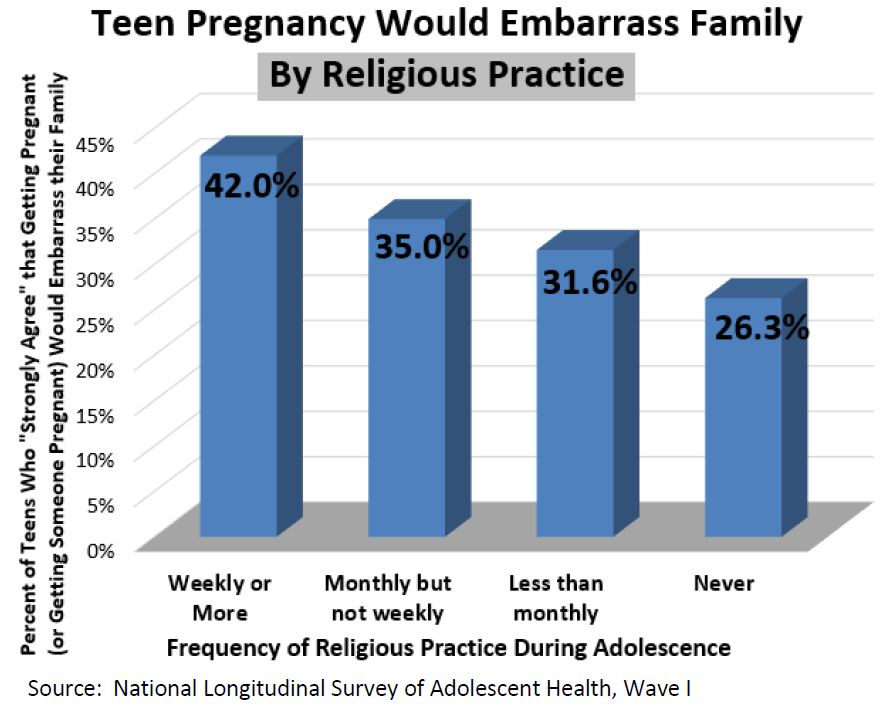

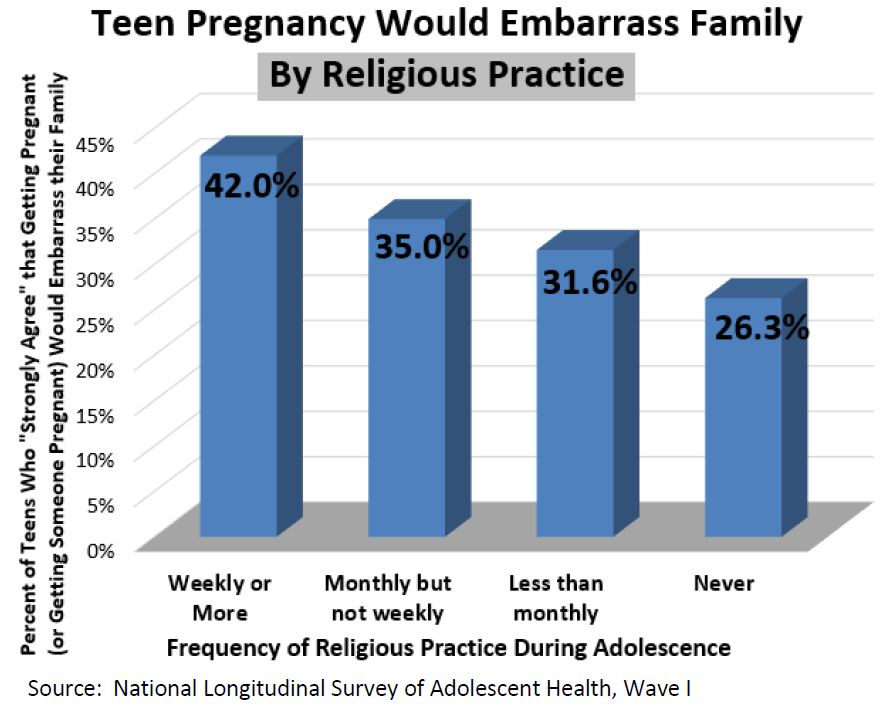

Religious Practice: Teens who frequently worshipped were more likely to strongly agree that getting pregnant (or getting someone pregnant) would embarrass their family. Thirteen- to nineteen-year-olds who attended religious services weekly or more often within the past year were more likely to believe that a pregnancy would embarrass their family (42.0 percent) than those who attended monthly but not weekly (35.0 percent), less than monthly (31.6 percent), or never (26.3 percent).

Family Structure and Religious Practice Combined:

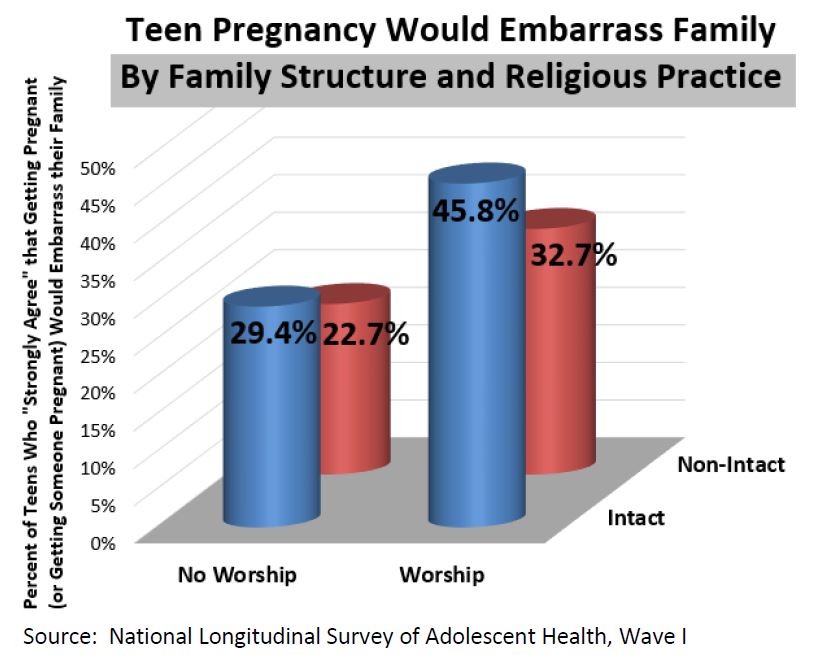

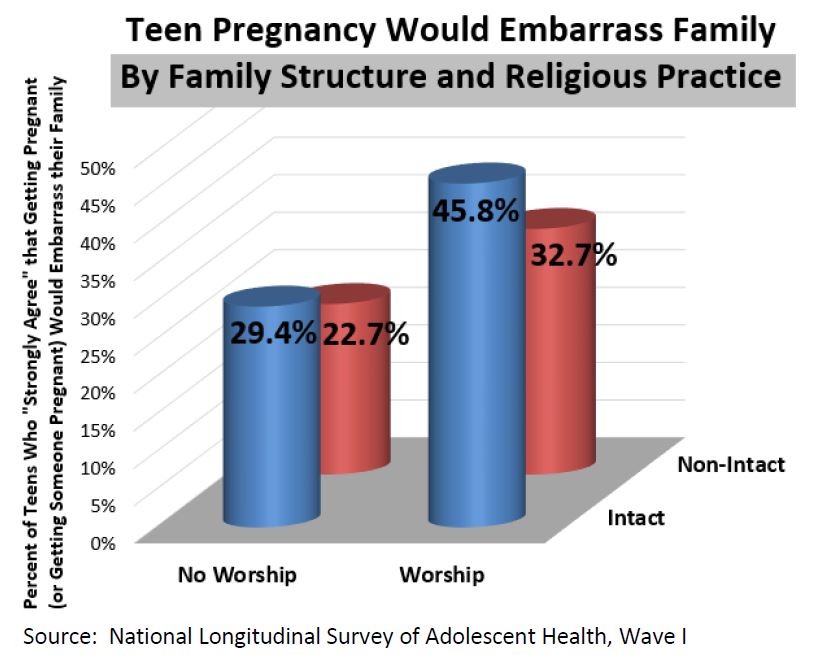

Family Structure and Religious Practice Combined: Thirteen- to nineteen-year-olds in intact worshipping families were most likely to strongly agree that getting pregnant or getting someone pregnant would embarrass their family (45.8 percent). Teens in intact non-worshipping families (29.4 percent) and non-intact worshipping families (32.7 percent) were less likely to believe that a pregnancy would embarrass their family. Teens in non-intact families that did not worship were least likely to think a pregnancy would bring embarrassment (22.7 percent).

Related Insights from Other Studies:

Related Insights from Other Studies: Family disapproval and embarrassment is an important sanction to discourage people from violating social norms.

[3] Research shows that both family structure and religious attendance form these norms. For instance, Les B. Whitbeck, Ronald L Simons, and Meei-Ying Kao found that sexual permissiveness of divorced parents significantly increases permissive attitudes in their children.

[4] On the other hand, family rules and parental supervision of dating are associated with teens not having sexual intercourse, a later sexual debut, and fewer sexual partners.

[5]

Likewise, religiosity establishes stricter sexual norms. Amy Burdette and Terrence Hill found that an increase in private religiosity is associated with a 93 percent reduction in the odds of sexual intercourse among 13-year-olds, and a 97 percent reduction in the odds of sexual debut for 17-year-olds.

[6]

[1] The charts draw on data collected by the National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health. The National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health (Add Health) is a congressionally-mandated longitudinal survey of American adolescents. Add Health drew a random sample of adolescents aged 13-19 in 1995 from junior high and high schools (Wave I) and has followed them in successive waves in 2001 (Wave III) and 2009 (Wave IV).

[2] Respondents were asked to react to the statement “If you got pregnant [males: if you got someone pregnant], it would be embarrassing for your family.” Their options included: “strongly agree,” “agree,” “neither agree nor disagree,” “disagree,” “strongly disagree,” “refused,” “don’t know,” or “not applicable.”

[3] Alexander Staller and Paolo Petta, “Introducing Emotions into the Computational Study of Social Norms: A First Evaluation,”

Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Stimulations 4 (2001).

[4] Les B. Whitbeck, Ronald L Simons, and Meei-Ying Kao, “The Effects of Divorced Mother’s Dating Behaviors and Sexual Attitudes on the Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors of Their Adolescent Children,”

Journal of Marriage and Family 56 (1994): 615-621.

[5] Brent C. Miller, “Family influences on adolescent sexual and contraceptive behavior,”

The Journal of Sex Research (2002): 22-26.

[6] Amy M. Burdette and Terrence D. Hill, “Religious Involvement and Transitions into Adolescent Sexual Activities,” (2009): 16.]]>

Religious Practice: Teens who frequently worshipped were more likely to strongly agree that getting pregnant (or getting someone pregnant) would embarrass their family. Thirteen- to nineteen-year-olds who attended religious services weekly or more often within the past year were more likely to believe that a pregnancy would embarrass their family (42.0 percent) than those who attended monthly but not weekly (35.0 percent), less than monthly (31.6 percent), or never (26.3 percent).

Religious Practice: Teens who frequently worshipped were more likely to strongly agree that getting pregnant (or getting someone pregnant) would embarrass their family. Thirteen- to nineteen-year-olds who attended religious services weekly or more often within the past year were more likely to believe that a pregnancy would embarrass their family (42.0 percent) than those who attended monthly but not weekly (35.0 percent), less than monthly (31.6 percent), or never (26.3 percent).

Family Structure and Religious Practice Combined: Thirteen- to nineteen-year-olds in intact worshipping families were most likely to strongly agree that getting pregnant or getting someone pregnant would embarrass their family (45.8 percent). Teens in intact non-worshipping families (29.4 percent) and non-intact worshipping families (32.7 percent) were less likely to believe that a pregnancy would embarrass their family. Teens in non-intact families that did not worship were least likely to think a pregnancy would bring embarrassment (22.7 percent).

Family Structure and Religious Practice Combined: Thirteen- to nineteen-year-olds in intact worshipping families were most likely to strongly agree that getting pregnant or getting someone pregnant would embarrass their family (45.8 percent). Teens in intact non-worshipping families (29.4 percent) and non-intact worshipping families (32.7 percent) were less likely to believe that a pregnancy would embarrass their family. Teens in non-intact families that did not worship were least likely to think a pregnancy would bring embarrassment (22.7 percent).

Related Insights from Other Studies: Family disapproval and embarrassment is an important sanction to discourage people from violating social norms.[3] Research shows that both family structure and religious attendance form these norms. For instance, Les B. Whitbeck, Ronald L Simons, and Meei-Ying Kao found that sexual permissiveness of divorced parents significantly increases permissive attitudes in their children.[4] On the other hand, family rules and parental supervision of dating are associated with teens not having sexual intercourse, a later sexual debut, and fewer sexual partners.[5]

Likewise, religiosity establishes stricter sexual norms. Amy Burdette and Terrence Hill found that an increase in private religiosity is associated with a 93 percent reduction in the odds of sexual intercourse among 13-year-olds, and a 97 percent reduction in the odds of sexual debut for 17-year-olds.[6]

[1] The charts draw on data collected by the National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health. The National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health (Add Health) is a congressionally-mandated longitudinal survey of American adolescents. Add Health drew a random sample of adolescents aged 13-19 in 1995 from junior high and high schools (Wave I) and has followed them in successive waves in 2001 (Wave III) and 2009 (Wave IV).

[2] Respondents were asked to react to the statement “If you got pregnant [males: if you got someone pregnant], it would be embarrassing for your family.” Their options included: “strongly agree,” “agree,” “neither agree nor disagree,” “disagree,” “strongly disagree,” “refused,” “don’t know,” or “not applicable.”

[3] Alexander Staller and Paolo Petta, “Introducing Emotions into the Computational Study of Social Norms: A First Evaluation,” Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Stimulations 4 (2001).

[4] Les B. Whitbeck, Ronald L Simons, and Meei-Ying Kao, “The Effects of Divorced Mother’s Dating Behaviors and Sexual Attitudes on the Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors of Their Adolescent Children,” Journal of Marriage and Family 56 (1994): 615-621.

[5] Brent C. Miller, “Family influences on adolescent sexual and contraceptive behavior,” The Journal of Sex Research (2002): 22-26.

[6] Amy M. Burdette and Terrence D. Hill, “Religious Involvement and Transitions into Adolescent Sexual Activities,” (2009): 16.]]>

Related Insights from Other Studies: Family disapproval and embarrassment is an important sanction to discourage people from violating social norms.[3] Research shows that both family structure and religious attendance form these norms. For instance, Les B. Whitbeck, Ronald L Simons, and Meei-Ying Kao found that sexual permissiveness of divorced parents significantly increases permissive attitudes in their children.[4] On the other hand, family rules and parental supervision of dating are associated with teens not having sexual intercourse, a later sexual debut, and fewer sexual partners.[5]

Likewise, religiosity establishes stricter sexual norms. Amy Burdette and Terrence Hill found that an increase in private religiosity is associated with a 93 percent reduction in the odds of sexual intercourse among 13-year-olds, and a 97 percent reduction in the odds of sexual debut for 17-year-olds.[6]

[1] The charts draw on data collected by the National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health. The National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health (Add Health) is a congressionally-mandated longitudinal survey of American adolescents. Add Health drew a random sample of adolescents aged 13-19 in 1995 from junior high and high schools (Wave I) and has followed them in successive waves in 2001 (Wave III) and 2009 (Wave IV).

[2] Respondents were asked to react to the statement “If you got pregnant [males: if you got someone pregnant], it would be embarrassing for your family.” Their options included: “strongly agree,” “agree,” “neither agree nor disagree,” “disagree,” “strongly disagree,” “refused,” “don’t know,” or “not applicable.”

[3] Alexander Staller and Paolo Petta, “Introducing Emotions into the Computational Study of Social Norms: A First Evaluation,” Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Stimulations 4 (2001).

[4] Les B. Whitbeck, Ronald L Simons, and Meei-Ying Kao, “The Effects of Divorced Mother’s Dating Behaviors and Sexual Attitudes on the Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors of Their Adolescent Children,” Journal of Marriage and Family 56 (1994): 615-621.

[5] Brent C. Miller, “Family influences on adolescent sexual and contraceptive behavior,” The Journal of Sex Research (2002): 22-26.

[6] Amy M. Burdette and Terrence D. Hill, “Religious Involvement and Transitions into Adolescent Sexual Activities,” (2009): 16.]]>