Click Here to download “Smoking Among Minors by Family Structure and Religious Practice”

Smoking Among Minors by Family Structure and Religious Practice

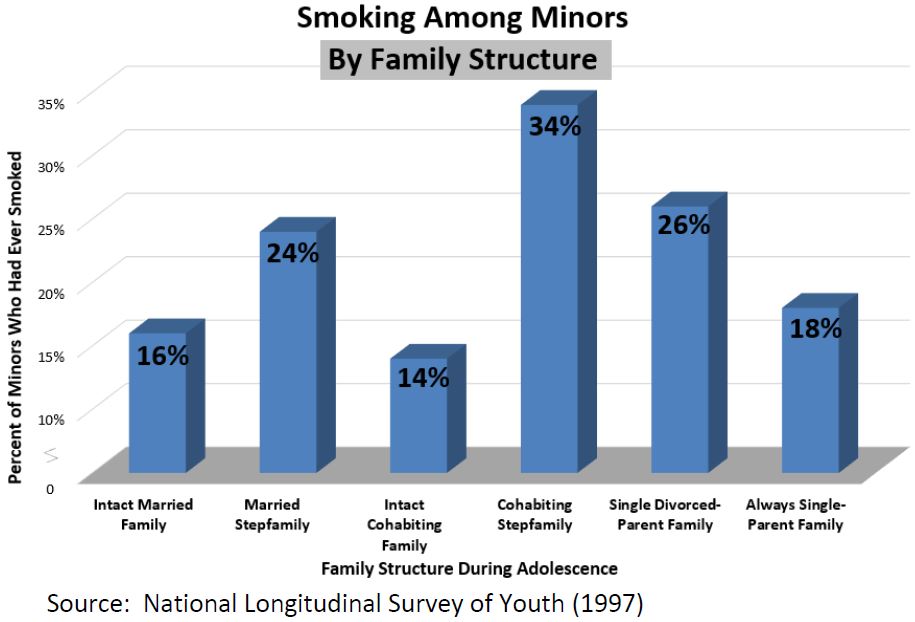

The 1997 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth shows that children under 17 who grew up in an intact married family and worshipped at least weekly at the time of the survey were less likely to smoke than were their peers from other family backgrounds. [1] Family Structure: 14 percent of children under the age of 17 who grew up in an intact, cohabiting stepfamily had ever smoked, followed by 16 percent of children from always-intact married families. Eighteen percent of children from always-single parent households had smoked, followed by 24 percent of children from married stepfamilies, 26 percent of children from single, divorced-parent families, and 34 percent of children from cohabiting stepfamilies. Religious Practice: 37 percent of children who attended religious services weekly had smoked, compared with those who attended between one and three times a month (45 percent), those who attended less than once a month (53 percent), and those who never attended religious services (55 percent).

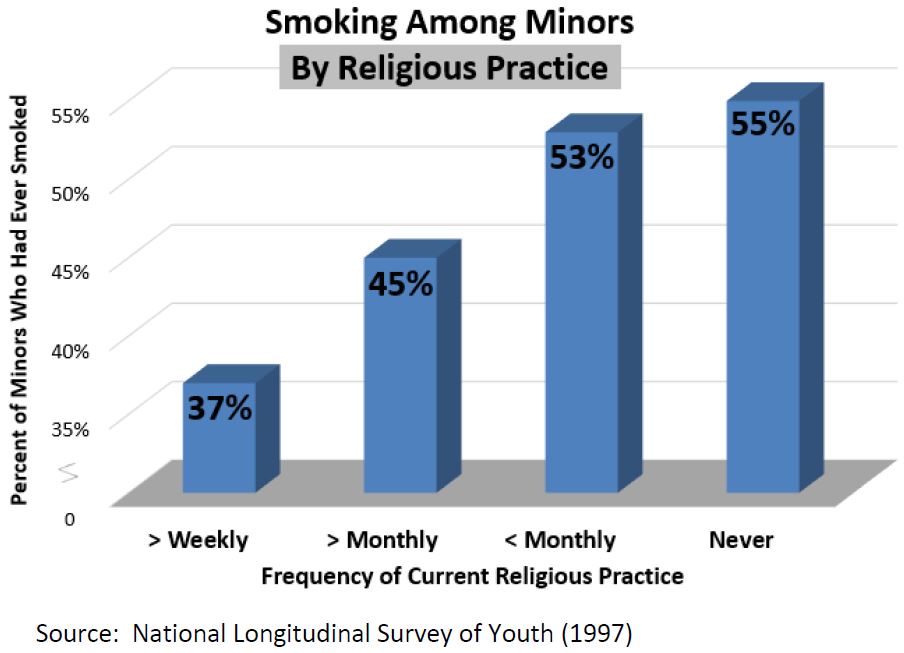

Religious Practice: 37 percent of children who attended religious services weekly had smoked, compared with those who attended between one and three times a month (45 percent), those who attended less than once a month (53 percent), and those who never attended religious services (55 percent).

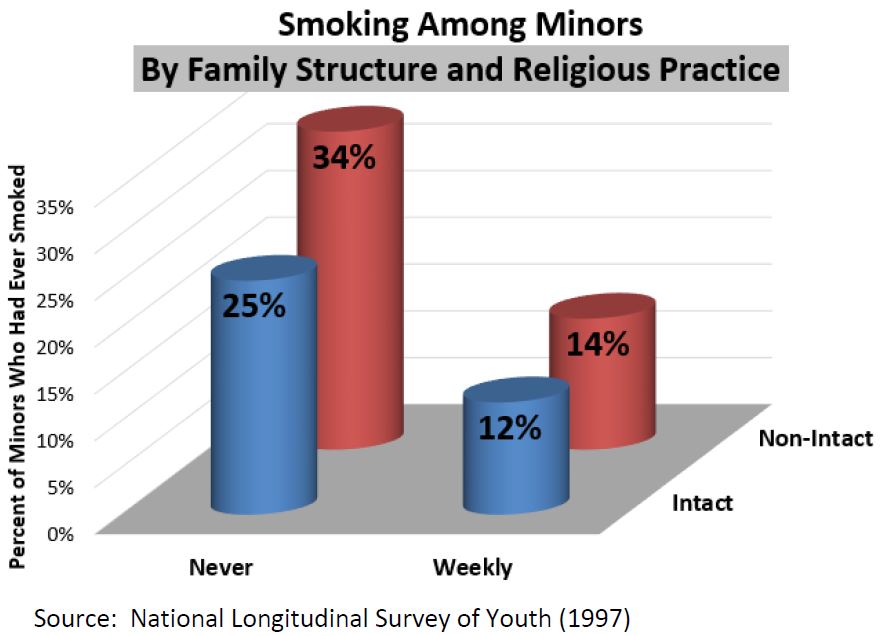

Family Structure and Religious Practice Combined: 12 percent of children who grew up in an intact married family and who worshipped at least weekly at the time of the survey had ever smoked. Only 14 percent who grew up in all other family structures but attended weekly religious services ever smoked, compared with 25 percent of those who grew up in always-intact families, but never attended church, and 34 percent of those who grew up in all other family structures and never attended church.

Family Structure and Religious Practice Combined: 12 percent of children who grew up in an intact married family and who worshipped at least weekly at the time of the survey had ever smoked. Only 14 percent who grew up in all other family structures but attended weekly religious services ever smoked, compared with 25 percent of those who grew up in always-intact families, but never attended church, and 34 percent of those who grew up in all other family structures and never attended church.

Related Insights from Other Studies: Family relationships play a significant role in determining the behavior of children, according to the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (CASA) at Columbia University’s “Back to School” survey. The survey found that frequent family dinners (five nights or more a week) were associated with lower rates of teen smoking, drinking, and drug use. Teens who had dinner with their families only twice a week or less were 2.5 times as likely to smoke cigarettes, more than 1.5 times as likely to drink alcohol, and nearly 3 times as likely to try marijuana.[2]

The effects of family structure were seen in a British longitudinal study which found that youths living in single-parent households were 1.5 times more likely to smoke.[3] The National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health agreed with the British study, showing that compared to their peers in single-parent families, middle school and high school students in two-parent families reported, on average, lower levels of smoking.[4]

Religious practice also affects teenagers’ habits. One survey showed that, compared with their peers, youths who said religion was important in their lives and/or attended religious services frequently were less likely to smoke. They were also less likely to use other substances or be sexually active.[5] Another study of adolescents and young women showed that women who said religion and spirituality were important in their lives were less likely than their peers to smoke or binge drink.[6]

[1] These charts draw on data collected by the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (1997).

[2] The National Center of Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, “The Importance of Family Dinners II” (2005).

[3] Ely, Margaret, Patrick West, Helen Sweeting and Martin Richards, “Teenage Family Life, Life Chances, Lifestyles and Health: A Comparison of Two Contemporary Cohorts” International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family (14)1 (2000) pp. 1-30.

[4] Blum, Robert W. and Trisha Beuhrign, “The Effects of Race/Ethnicity, Income, and Family Structure on Adolescent Risk Behaviors,” American Journal of Public Health (90)12 (2000) pp. 1879-1884.

[5] Sinha, J. W., R. Cnaan and R.J. Gelles, “Adolescent risk behaviors and religion: Findings from a national study,” Journal of Adolescence (30) (2007) pp. 231-249.

[6] Pirkle, Erin C. and Linda Richter,”Personality, attitudinal and behavioral risk profiles of young female binge drinkers and smokers,” Journal of Adolescent Health (38) (2006) pp. 44-54.]]>

Related Insights from Other Studies: Family relationships play a significant role in determining the behavior of children, according to the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (CASA) at Columbia University’s “Back to School” survey. The survey found that frequent family dinners (five nights or more a week) were associated with lower rates of teen smoking, drinking, and drug use. Teens who had dinner with their families only twice a week or less were 2.5 times as likely to smoke cigarettes, more than 1.5 times as likely to drink alcohol, and nearly 3 times as likely to try marijuana.[2]

The effects of family structure were seen in a British longitudinal study which found that youths living in single-parent households were 1.5 times more likely to smoke.[3] The National Longitudinal Survey of Adolescent Health agreed with the British study, showing that compared to their peers in single-parent families, middle school and high school students in two-parent families reported, on average, lower levels of smoking.[4]

Religious practice also affects teenagers’ habits. One survey showed that, compared with their peers, youths who said religion was important in their lives and/or attended religious services frequently were less likely to smoke. They were also less likely to use other substances or be sexually active.[5] Another study of adolescents and young women showed that women who said religion and spirituality were important in their lives were less likely than their peers to smoke or binge drink.[6]

[1] These charts draw on data collected by the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (1997).

[2] The National Center of Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, “The Importance of Family Dinners II” (2005).

[3] Ely, Margaret, Patrick West, Helen Sweeting and Martin Richards, “Teenage Family Life, Life Chances, Lifestyles and Health: A Comparison of Two Contemporary Cohorts” International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family (14)1 (2000) pp. 1-30.

[4] Blum, Robert W. and Trisha Beuhrign, “The Effects of Race/Ethnicity, Income, and Family Structure on Adolescent Risk Behaviors,” American Journal of Public Health (90)12 (2000) pp. 1879-1884.

[5] Sinha, J. W., R. Cnaan and R.J. Gelles, “Adolescent risk behaviors and religion: Findings from a national study,” Journal of Adolescence (30) (2007) pp. 231-249.

[6] Pirkle, Erin C. and Linda Richter,”Personality, attitudinal and behavioral risk profiles of young female binge drinkers and smokers,” Journal of Adolescent Health (38) (2006) pp. 44-54.]]>