Click Here to download “Smoking Among Adults by Family Structure and Religious Practice”

Smoking Among Adults by Family Structure and Religious Practice

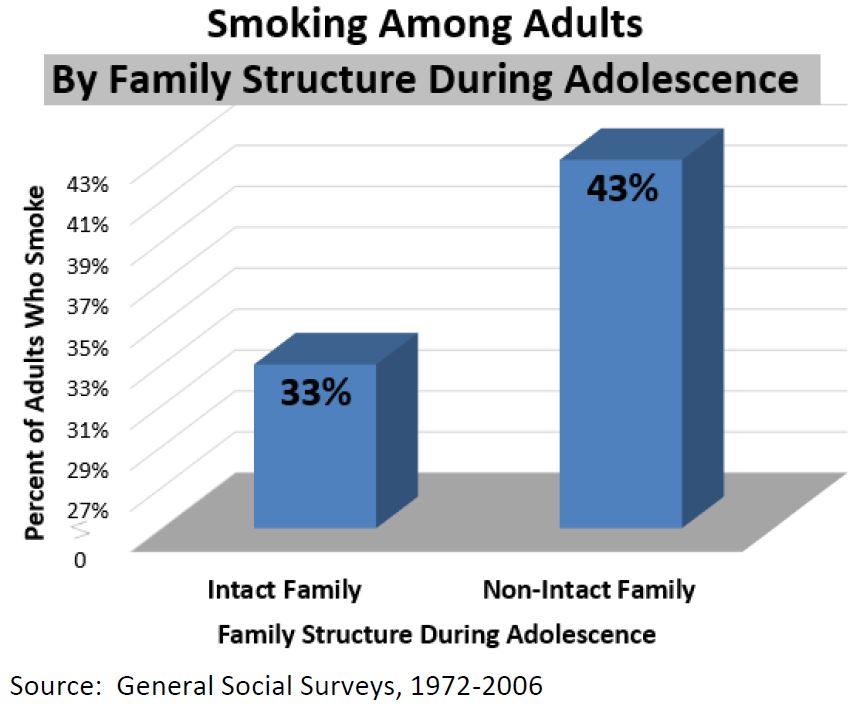

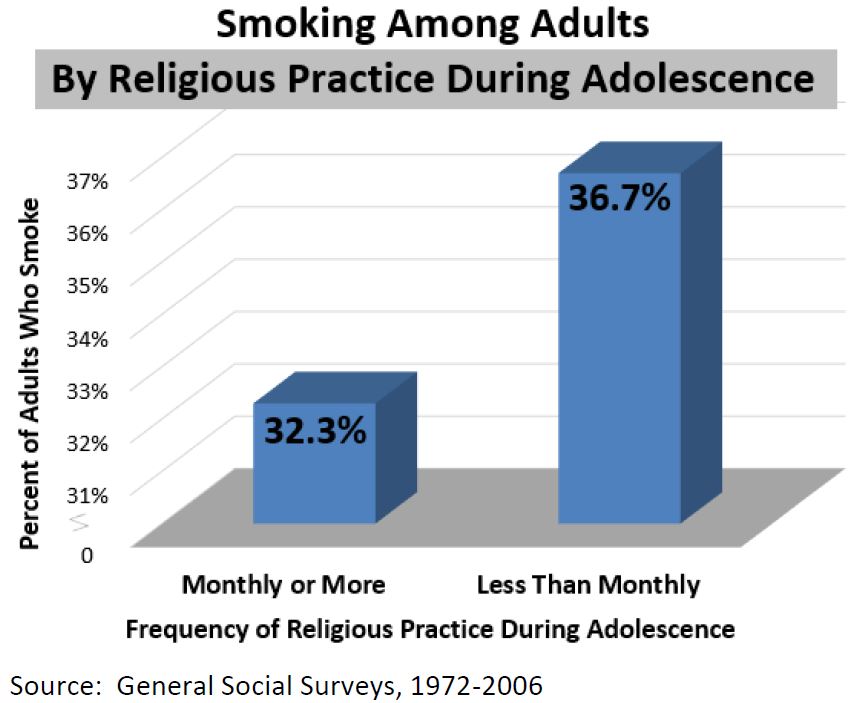

Family Structure: Adults who grew up living with both biological parents are less likely to smoke than those who did not. According to the General Social Surveys (GSS), 33 percent of adults who lived in an intact family during adolescence smoke, compared to 43 percent of those who lived in a non-intact family. Religious Practice: Adults who frequently attended religious services as adolescents are less likely to smoke than those who did not. According to the General Social Surveys (GSS), 32.3 percent of adults who attended religious services at least monthly as adolescents smoke, compared to 36.7 percent of those who worshiped less frequently.

Religious Practice: Adults who frequently attended religious services as adolescents are less likely to smoke than those who did not. According to the General Social Surveys (GSS), 32.3 percent of adults who attended religious services at least monthly as adolescents smoke, compared to 36.7 percent of those who worshiped less frequently.

Family Structure and Religious Practice Combined: Adults who frequently attended religious services as adolescents and grew up living with both biological parents are least likely to smoke. According to the General Social Surveys (GSS), 31 percent of adults who attended religious services at least monthly and lived in an intact family through adolescence currently smoke, compared to 44 percent of those who attended religious services less than monthly and grew up in a non-intact family. In between were those who attended religious services at least monthly but lived in a non-intact family (42 percent) and those who grew up in an intact family but worshiped less than monthly (36 percent).

Family Structure and Religious Practice Combined: Adults who frequently attended religious services as adolescents and grew up living with both biological parents are least likely to smoke. According to the General Social Surveys (GSS), 31 percent of adults who attended religious services at least monthly and lived in an intact family through adolescence currently smoke, compared to 44 percent of those who attended religious services less than monthly and grew up in a non-intact family. In between were those who attended religious services at least monthly but lived in a non-intact family (42 percent) and those who grew up in an intact family but worshiped less than monthly (36 percent).

Related Insights from Other Studies: Though a paucity of research exists on the correlation between adolescent religious attendance and adult smoking, many other studies demonstrate a contemporaneous association between religious attendance and smoking.

Analyzing the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, Mary Whooley of the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center and colleagues found that “greater frequency of attendance at religious services was associated with less current smoking.” Only 17 percent of young adults who attend church at least weekly smoke, compared to 23 percent of those who attend at least once a month and 34 percent of those who attend less than once a month or never. Among smokers, those who attend church more frequently smoke fewer cigarettes per day than those who attend less frequently.[1]

Nancy Kaufman of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and colleagues also reported a significant association between “lack of attendance in religious activities” and regular smoking.[2]

In a study of Australians, Andrew Heath of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis found that “low religious involvement” predicted the initiation of smoking in both men and women.[3]

Kenneth Kendler of the Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Medical Genetics reported an association between personal religious devotion and a lesser chance of lifetime regular smoking.[4]

And John Tauras of the University of Illinois at Chicago found that among young adults who smoke, those who frequently attend religious services “are much more likely to quit smoking.”[5]

As the evidence demonstrates, frequent religious attendance reduces rates of smoking.

Though little related research exists on intergenerational links between family structure during adolescence and adult smoking, many other studies show a contemporaneous correlation between adolescent family structure and smoking.

In a study of adolescents from 11 European countries, Thoroddur Bjarnason at the State University of New York at Albany and colleagues reported that “adolescents who live with both biological parents smoke less than those living with single mothers, who in turn smoke less than those living with single fathers, mothers-stepfathers, or with neither biological parent.”[6]

Joan Tucker of RAND and colleagues found that “early experimenters were more likely than were nonsmokers” to live in a non-intact family.[7]

Tucker and colleagues also reported that male adolescent and young adult smokers who did not live in an intact nuclear family were less likely to quit smoking.[8]

Examining the smoking habits of adults in various family structures, Mark Schuster of the University of California, Los Angeles and colleagues reported that 33 percent of homes with at least two adults have regular smokers, compared to 46 percent of mother-only homes and 43 percent of father-only homes.[9]

As the data clearly show, intact families yield the lowest percentage of smokers.

Several other studies corroborate the direction of these findings. In a study of Australian twins, Arpana Agrawal of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and colleagues found that infrequent religious attendance correlated with frequent cigarette smoking and that “children separated from a biological parent were…more likely to report regular cigarette smoking as adults.”[10]

Analyzing various degrees of smoking in adolescents, Stephen Soldz and Xingjia Cui of Health and Addictions Research reported that nonsmokers attended religious services most frequently, whereas early escalator smokers attended less frequently and continuous smokers least frequently. They also found that at the sixth grade in school, “quitters and experimenters were more likely to be living with both parents, whereas late escalators and continuous smokers were more likely to be living with a single parent or an extended family.”[11]

Thomas Wills of Yeshiva University and colleagues also found that adolescents’ religiosity was inversely correlated with tobacco use and that adolescents from intact families were less likely to use tobacco than those from blended and single-parent families.[12]

[1] Mary A. Whooley, et al., “Religious Involvement and Cigarette Smoking in Young Adults,” Archives of Internal Medicine, vol. 162 (2002): 1,604-1,610.

[2] Nancy J. Kaufman, et al., “Predictors of Change on the Smoking Uptake Continuum among Adolescents,” Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, vol. 156 (2002): 581-587.

[3] Andrew C. Heath, et al., “Personality and the Inheritance of Smoking Behavior: A Genetic Perspective,” Behavior Genetics, vol. 25 (1995): 103-117.

[4] Kenneth S. Kendler, et al., “Religion, Psychopathology, and Substance Use and Abuse: A Multimeasure, Genetic-Epidemiologic Study,” American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 154 (1997): 322-329.

[5] John A. Tauras, “Public Policy and Smoking Cessation among Young Adults in the United States,” Health Policy, vol. 68 (2004): 321-332.

[6] Thoroddur Bjarnason, “Family Structure and Adolescent Cigarette Smoking in Eleven European Countries,” Addiction, vol. 98 (2003): 815-824.

[7] Joan S. Tucker, et al., “Five-Year Prospective Study of Risk Factors for Daily Smoking in Adolescence among Early Nonsmokers and Experimenters,” Journal of Applied Social Psychology, vol. 32 (2002): 1,588-1,603.

[8] Joan S. Tucker, et al., “Smoking Cessation during the Transition from Adolescence to Young Adulthood,” Nicotine & Tobacco Research, vol. 4 (2002): 321-332.

[9] Mark A. Schuster, et al., “Smoking Patterns of Household Members and Visitors in Homes with Children in the United States ,” Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, vol. 156 (2002): 1,094-1,100.

[10] Arpana Agrawal, et al., “Correlates of Regular Cigarette Smoking in a Population-based Sample of Australian Twins,” Addiction, vol. 100 (2005): 1,709-1,719.

[11] Stephen Soldz and Xingjia Cui, “Pathways through Adolescent Smoking: A 7-Year Longitudinal Grouping Analysis,” Health Psychology, vol. 21 (2002): 495-504.

[12] Thomas Ashby Wills, et al., “Buffering Effect of Religiosity for Adolescent Substance Use,” Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, vol. 17 (2003): 24-31.]]>

Related Insights from Other Studies: Though a paucity of research exists on the correlation between adolescent religious attendance and adult smoking, many other studies demonstrate a contemporaneous association between religious attendance and smoking.

Analyzing the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study, Mary Whooley of the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center and colleagues found that “greater frequency of attendance at religious services was associated with less current smoking.” Only 17 percent of young adults who attend church at least weekly smoke, compared to 23 percent of those who attend at least once a month and 34 percent of those who attend less than once a month or never. Among smokers, those who attend church more frequently smoke fewer cigarettes per day than those who attend less frequently.[1]

Nancy Kaufman of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and colleagues also reported a significant association between “lack of attendance in religious activities” and regular smoking.[2]

In a study of Australians, Andrew Heath of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis found that “low religious involvement” predicted the initiation of smoking in both men and women.[3]

Kenneth Kendler of the Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Medical Genetics reported an association between personal religious devotion and a lesser chance of lifetime regular smoking.[4]

And John Tauras of the University of Illinois at Chicago found that among young adults who smoke, those who frequently attend religious services “are much more likely to quit smoking.”[5]

As the evidence demonstrates, frequent religious attendance reduces rates of smoking.

Though little related research exists on intergenerational links between family structure during adolescence and adult smoking, many other studies show a contemporaneous correlation between adolescent family structure and smoking.

In a study of adolescents from 11 European countries, Thoroddur Bjarnason at the State University of New York at Albany and colleagues reported that “adolescents who live with both biological parents smoke less than those living with single mothers, who in turn smoke less than those living with single fathers, mothers-stepfathers, or with neither biological parent.”[6]

Joan Tucker of RAND and colleagues found that “early experimenters were more likely than were nonsmokers” to live in a non-intact family.[7]

Tucker and colleagues also reported that male adolescent and young adult smokers who did not live in an intact nuclear family were less likely to quit smoking.[8]

Examining the smoking habits of adults in various family structures, Mark Schuster of the University of California, Los Angeles and colleagues reported that 33 percent of homes with at least two adults have regular smokers, compared to 46 percent of mother-only homes and 43 percent of father-only homes.[9]

As the data clearly show, intact families yield the lowest percentage of smokers.

Several other studies corroborate the direction of these findings. In a study of Australian twins, Arpana Agrawal of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and colleagues found that infrequent religious attendance correlated with frequent cigarette smoking and that “children separated from a biological parent were…more likely to report regular cigarette smoking as adults.”[10]

Analyzing various degrees of smoking in adolescents, Stephen Soldz and Xingjia Cui of Health and Addictions Research reported that nonsmokers attended religious services most frequently, whereas early escalator smokers attended less frequently and continuous smokers least frequently. They also found that at the sixth grade in school, “quitters and experimenters were more likely to be living with both parents, whereas late escalators and continuous smokers were more likely to be living with a single parent or an extended family.”[11]

Thomas Wills of Yeshiva University and colleagues also found that adolescents’ religiosity was inversely correlated with tobacco use and that adolescents from intact families were less likely to use tobacco than those from blended and single-parent families.[12]

[1] Mary A. Whooley, et al., “Religious Involvement and Cigarette Smoking in Young Adults,” Archives of Internal Medicine, vol. 162 (2002): 1,604-1,610.

[2] Nancy J. Kaufman, et al., “Predictors of Change on the Smoking Uptake Continuum among Adolescents,” Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, vol. 156 (2002): 581-587.

[3] Andrew C. Heath, et al., “Personality and the Inheritance of Smoking Behavior: A Genetic Perspective,” Behavior Genetics, vol. 25 (1995): 103-117.

[4] Kenneth S. Kendler, et al., “Religion, Psychopathology, and Substance Use and Abuse: A Multimeasure, Genetic-Epidemiologic Study,” American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 154 (1997): 322-329.

[5] John A. Tauras, “Public Policy and Smoking Cessation among Young Adults in the United States,” Health Policy, vol. 68 (2004): 321-332.

[6] Thoroddur Bjarnason, “Family Structure and Adolescent Cigarette Smoking in Eleven European Countries,” Addiction, vol. 98 (2003): 815-824.

[7] Joan S. Tucker, et al., “Five-Year Prospective Study of Risk Factors for Daily Smoking in Adolescence among Early Nonsmokers and Experimenters,” Journal of Applied Social Psychology, vol. 32 (2002): 1,588-1,603.

[8] Joan S. Tucker, et al., “Smoking Cessation during the Transition from Adolescence to Young Adulthood,” Nicotine & Tobacco Research, vol. 4 (2002): 321-332.

[9] Mark A. Schuster, et al., “Smoking Patterns of Household Members and Visitors in Homes with Children in the United States ,” Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, vol. 156 (2002): 1,094-1,100.

[10] Arpana Agrawal, et al., “Correlates of Regular Cigarette Smoking in a Population-based Sample of Australian Twins,” Addiction, vol. 100 (2005): 1,709-1,719.

[11] Stephen Soldz and Xingjia Cui, “Pathways through Adolescent Smoking: A 7-Year Longitudinal Grouping Analysis,” Health Psychology, vol. 21 (2002): 495-504.

[12] Thomas Ashby Wills, et al., “Buffering Effect of Religiosity for Adolescent Substance Use,” Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, vol. 17 (2003): 24-31.]]>