Click Here to download “Child Behavioral Problems by Family Structure and Religious Practice”

Child Behavioral Problems by Family Structure and Religious Practice

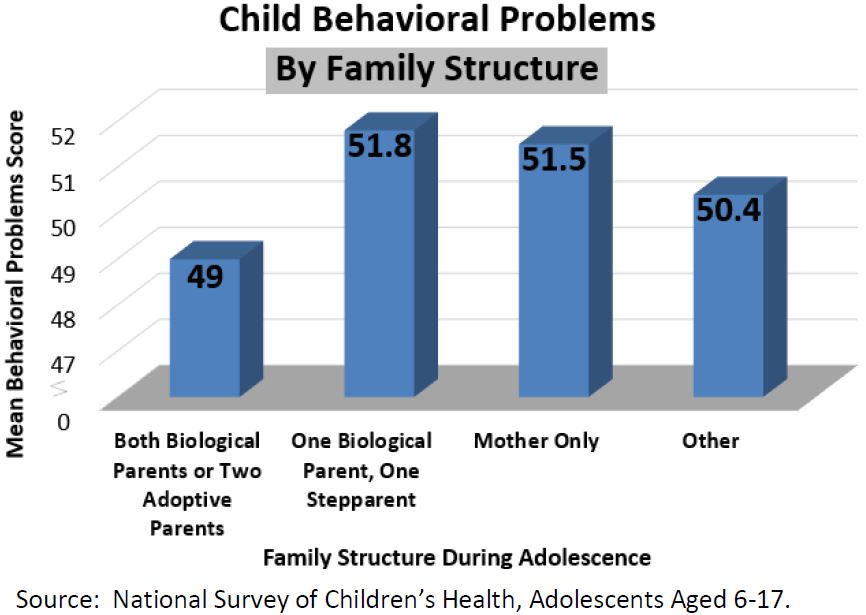

Family Structure: According to the National Survey of Children’s Health, children who lived with both biological parents scored lower on the behavior problems scale (49.0)[1] than those who lived with a biological parent and a stepparent (51.8).[2] In between were those who only lived with their biological mother (51.5) or those who lived within another family structure (50.4).[3] Items measured on the behavior problems scale included bullying, disobedience, and acting depressed.[4] Religious Practice: According to the National Survey of Children’s Health, children who attended religious services at least weekly scored lower on the behavior problems scale (49.2) than those who never attended religious services (51.8).[5] In between were those who worshipped one to three times a month (50.4) and those who attended religious services less than once a month (51.1). Items measured on the behavior problems scale included bullying, disobedience, and acting depressed.

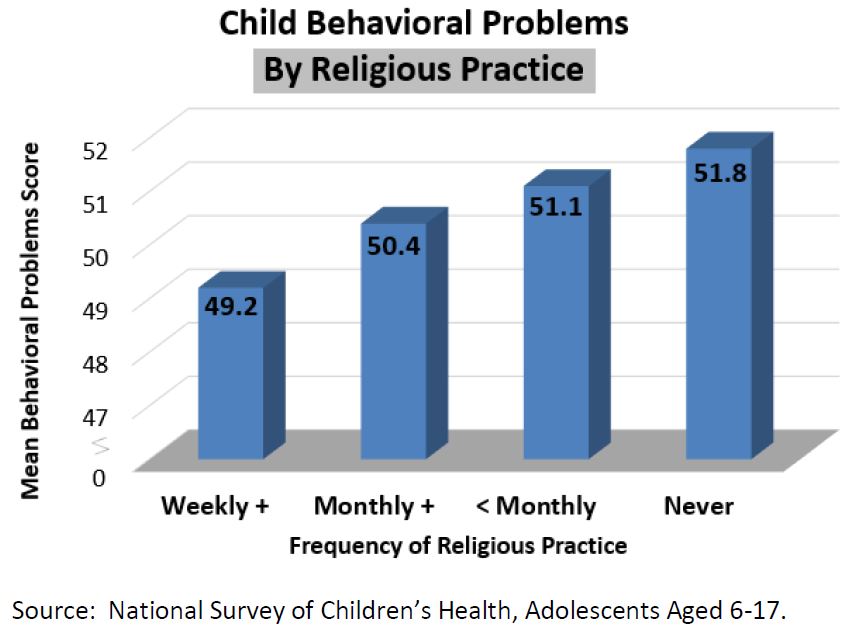

Religious Practice: According to the National Survey of Children’s Health, children who attended religious services at least weekly scored lower on the behavior problems scale (49.2) than those who never attended religious services (51.8).[5] In between were those who worshipped one to three times a month (50.4) and those who attended religious services less than once a month (51.1). Items measured on the behavior problems scale included bullying, disobedience, and acting depressed.

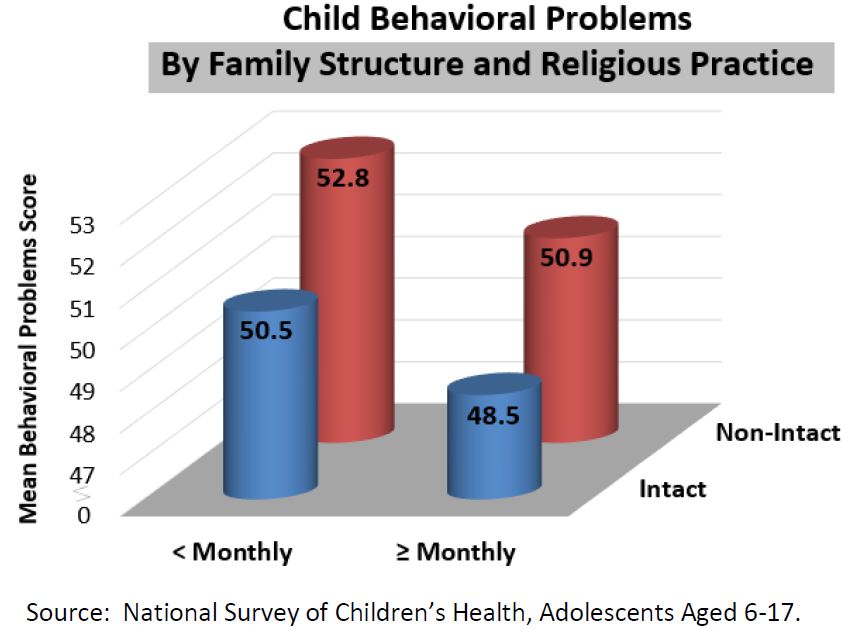

Family Structure and Religious Practice Combined: Children who worshipped frequently and lived with both biological parents or with two adoptive parents had a lower score (48.5) than those who worshipped less than monthly and lived in single-parent or reconstituted families (52.8). In between were those who lived in non-intact families who worshipped at least monthly (50.9) and those who lived in intact families and worshipped less than monthly (50.5). The data were taken from the National Survey of Children’s Health. Items measured on the behavior problems scale included bullying, disobedience, and acting depressed.

Family Structure and Religious Practice Combined: Children who worshipped frequently and lived with both biological parents or with two adoptive parents had a lower score (48.5) than those who worshipped less than monthly and lived in single-parent or reconstituted families (52.8). In between were those who lived in non-intact families who worshipped at least monthly (50.9) and those who lived in intact families and worshipped less than monthly (50.5). The data were taken from the National Survey of Children’s Health. Items measured on the behavior problems scale included bullying, disobedience, and acting depressed.

Related Insights from Other Studies: Several other studies support the direction of these findings. Marjorie Gunnoe of Calvin College and colleagues reported a strong association between adolescent responsibility and parental religiosity and noted how previous studies have shown “that parents play an active role in fostering adolescents’ attachment to the religious community.”[6]

John Bartkowski of Mississippi State University and colleagues found that frequent religious attendance of both parents correlated with a wide range of positive outcomes in their children, including greater self-control, greater interpersonal skills at school, greater social skills, protection against loneliness/sadness, protection “against internalizing problem behaviors,” protection from overactive and impulsive behaviors in the home, and a lower probability of “externalizing problem behaviors at school.”[7]

Jerry Trusty of Texas A&M University and Richard Watts of Baylor University also found that high school seniors who frequently attended religious activities were more likely to have involved parents and less likely to be delinquent than those high school seniors who attended religious activities less frequently.[8]

The twin protective forces of an intact married family and religious attendance both contribute significantly to the cultivation of appropriate adolescent behavior.

[1] A small sample of “two adoptive parents” is also included in this score.

[2] Most of the parents in the “biological parent and a stepparent” category are married.

[3] Categories covered under “other” include children with father only, foster parent, and children living with grandparent or other relatives.

[4] The behavior problems scale has a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of ten.

[5] The behavior problems scale has a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of ten.

[6] Marjorie Lindner Gunnoe, et al., “Parental Religiosity, Parenting Style, and Adolescent Social Responsibility,” Journal of Early Adolescence 19 (1999): 199-225.

[7] John P. Bartowski, et al., “Religion and Child Development: Evidence from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study,” Social Science Research 37 (2008): 18-36.

[8] Jerry Trusty and Richard E. Watts, “Relationship of High School Seniors’ Religious Perceptions and Behavior to Educational, Career, and Leisure Variables,” Counseling and Values 44 (1999): 30-40. This finding is from www.familyfacts.org.

]]>

Related Insights from Other Studies: Several other studies support the direction of these findings. Marjorie Gunnoe of Calvin College and colleagues reported a strong association between adolescent responsibility and parental religiosity and noted how previous studies have shown “that parents play an active role in fostering adolescents’ attachment to the religious community.”[6]

John Bartkowski of Mississippi State University and colleagues found that frequent religious attendance of both parents correlated with a wide range of positive outcomes in their children, including greater self-control, greater interpersonal skills at school, greater social skills, protection against loneliness/sadness, protection “against internalizing problem behaviors,” protection from overactive and impulsive behaviors in the home, and a lower probability of “externalizing problem behaviors at school.”[7]

Jerry Trusty of Texas A&M University and Richard Watts of Baylor University also found that high school seniors who frequently attended religious activities were more likely to have involved parents and less likely to be delinquent than those high school seniors who attended religious activities less frequently.[8]

The twin protective forces of an intact married family and religious attendance both contribute significantly to the cultivation of appropriate adolescent behavior.

[1] A small sample of “two adoptive parents” is also included in this score.

[2] Most of the parents in the “biological parent and a stepparent” category are married.

[3] Categories covered under “other” include children with father only, foster parent, and children living with grandparent or other relatives.

[4] The behavior problems scale has a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of ten.

[5] The behavior problems scale has a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of ten.

[6] Marjorie Lindner Gunnoe, et al., “Parental Religiosity, Parenting Style, and Adolescent Social Responsibility,” Journal of Early Adolescence 19 (1999): 199-225.

[7] John P. Bartowski, et al., “Religion and Child Development: Evidence from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study,” Social Science Research 37 (2008): 18-36.

[8] Jerry Trusty and Richard E. Watts, “Relationship of High School Seniors’ Religious Perceptions and Behavior to Educational, Career, and Leisure Variables,” Counseling and Values 44 (1999): 30-40. This finding is from www.familyfacts.org.

]]>